Thursday, December 30, 2021

CRT AND PALESTINE

THE ABSURD TIMES

When LBJ was asked why he didn't fire Hoover, he replied "AH'D RATHER HAVE HIM INSIDE THE TENT PISSING OUT, THAN OUTSIDE PISSING IN/' That was the best he came up with.

CRT AND PALESTINE

BY

HONEST CHARLIE

I have not counted, but I have pointed out that the only person I know of who can present and discuss Critical Race Theory is Angela Davis. This is because she studied for her Doctorate with Adorno and then finished here with Hibbermas. This is all Critical Theory, once functioning in Frankfurt, Germany and Horkheimer, in his ECLIPSE OF REASON, made world known. Horkheimer did not really like the idea, but it came to be called the Frankfurt School.

It is a long known line of thought that left Germany as Hitler was coming to power in Germany. Hitler stared off by killing "Communists," then Marxists, then anyone else he didn't like, especially Jews.

Well, Angela was in France when four little girls were burned to death in the U.S. south, probably Alabama. That is why she finished her dissertation with Habermas.

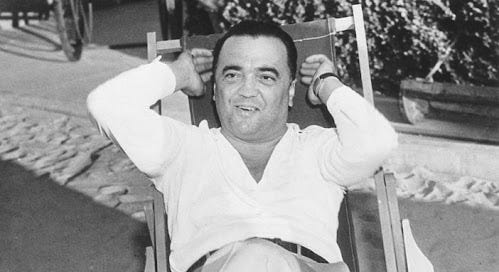

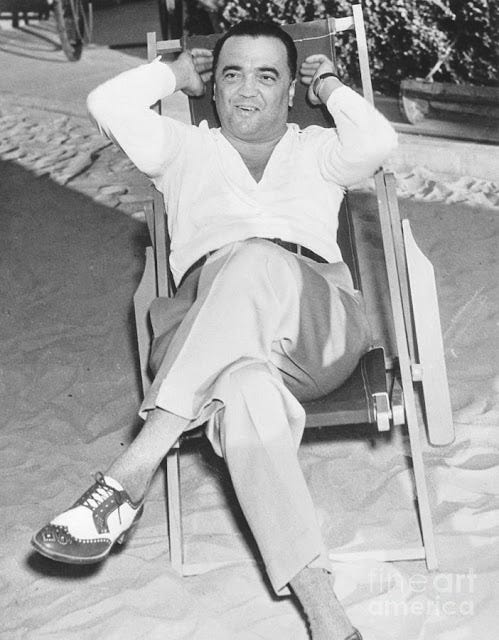

J. Edgar Hoover, head of the FBI and sometimes called vacuum cleaner salesman, people say, liked to dress in his mother’s underwear and chase after his male secretary. The one thing he did do, it is established, was put her on the FBI’S MOST WANTED LIST. This was new to me, but the sign is still available online somewhere. She is now Professor Emeritus at the University of California.

Essentially, she dismisses CRT, then talks about Palestine, and what needs to come next. Here it is:

World-renowned author, activist and professor Angela Davis talks about the prison abolition movement from her time as a Black Panther leader to today. In her tireless efforts as an abolitionist and a teacher, Davis continues to be a fierce advocate of education and the interconnected struggles of oppressed peoples. Davis talks about Indigenous genocide, Palestine, critical race theory and the role of independent media. “Democracy Now! helps us to place our own domestic issues and struggles within the context of global battles against fascism,” says Davis.

Transcript

This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org. I’m Amy Goodman. Well, this year we’ve been marking Democracy Now!’s 25th anniversary on the air. Earlier this month, Angela Davis, Noam Chomsky, Arundhati Roy, Martín Espada, Winona LaDuke, Danny Glover, Danny DeVito and others joined us for a virtual anniversary celebration. You can watch the whole event at democracynow.org.

Today, we bring you our full conversation with Angela Davis, the world-renowned abolitionist, author, activist and professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz. Democracy Now!’s Juan González and I interviewed her from her home in Oakland, California.

AMY GOODMAN: On this 25th anniversary celebration, Angela, it is such an honor to have you join us, as you’ve done so many times in the last decades.

ANGELA DAVIS: Well, thank you so much, Amy. You know, it seems like it’s been longer than 25 years. It seems like Democracy Now! has always been there. But I think I may also be thinking about I.F. Stone’s newsletter and some other progressive media in your lineage.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, to be counted in that amazing pantheon, someone like I.F. Stone, who said to journalism students, “If you can remember two words, remember 'governments lie.' If you can remember three words, remember 'all governments lie,'” it would be an honor for us to be counted together with I.F. Stone.

ANGELA DAVIS: Well, thank you so much for your work over the years. I was just reflecting on the fact that when no one else would cover Mumia Abu-Jamal, we were able to hear his voice on Democracy Now! And when no one else was thinking about Assata Shakur and the demonization of Assata Shakur, Amy, you and Juan and your colleagues were covering her case. So thank you so much. I don’t know what we would have been able to do in our efforts to push for radical social change if Democracy Now! had not been there.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Well, Angela, I wanted to ask you — when we first spoke on Democracy Now! about abolishing about the prison-industrial complex, that was back in 2010. And you said then that, quote, “Prison abolition is about building a new world.” Here we are more than a decade later. The abolition movement has drawn more attention. What is key to understand about how this movement can continue to grow?

ANGELA DAVIS: Well, you know, let’s remember that the abolition movement has a very long genealogy. We can go back to the 1970s and the Attica brothers uprising. The people in prison there who rose up against the horrendous conditions also called for prison abolition.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: That’s right.

ANGELA DAVIS: This was perhaps the first time that there was this public display of a way to address the prison system that was not couched in the ideology of reform.

I am absolutely surprised that abolition has entered into public discourse during this period. To tell the truth, many of my comrades and I assumed that it would be decades and decades, you know, perhaps 50 years from now, people would finally begin to understand that we cannot keep attempting to reform the police or reform the prisons. Reform is actually the glue that has held these institutions together over the years.

But it’s so exciting now to see young people, especially, talking about building a new world, recognizing that it’s not about punishing this person and that person, it’s about creating a new framework so that we do not have to depend on institutions like the police and prisons for safety and security. We can learn how to depend on education and healthcare and mental healthcare and recreation and all of the things that human beings need in order to flourish. That is true security, true safety.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: I wanted to ask you about another aspect of that movement, as well. You’re the daughter of civil rights activists. You went on to become a prominent member of the Communist Party USA, a leader of the Black Panther Party. And you were targeted by the FBI. At one point, the FBI had you on its list of the 10 most wanted fugitives in America. Yet today, some of the loudest voices within the young radical resurgence in America, especially on the college campuses and in middle-class intellectual circles, are openly dismissive or simply ignorant of the most vital lessons of the Panther Party, the Young Lords and figures like Malcolm X, you and W.E.B. Du Bois, who all urged the need not only to battle systemic racism but also to strive for the solidarity of oppressed people of all races, for unity of workers against imperialism. But this new trend now, it seems to me, is focusing more on racial identity, individual biases and anti-Blackness as the central question for social change. And in doing so, they echo a historical strain of narrow nationalism, what we used to call in the Young Lords back then “pork chop nationalism.” The Panther Party, as well, called it that. Some have even sought on social media to cancel you and the lived experience and the sacrifices of radical socialists and the revolutionary movement within the Black and Brown communities. I’m wondering your thoughts on that? I’ve heard you speak on it, I think, at a forum in Germany recently.

ANGELA DAVIS: Well, yes. Yeah, I’m very disappointed that we don’t have a more capacious public understanding of what it means to stand up against racism, that racism is the very foundation of this country, based on colonialism and slavery. And that means, in the very first place, it is important to recognize the connections between Indigenous people and people of African descent. It is not possible to tell the story of people of African descent in the Americas without also telling the story of Indigenous people.

You know, I think that when we engage in serious conversations with young people who really want to learn, they begin to get it. They begin to recognize that we can’t work with these narrow assumptions about Blackness and who counts as Black and the efforts to dismiss what is often referred to as political Blackness. And, of course, Du Bois taught us so many decades ago that the reason for identifying connections and relationalities among African people and people of African descent has little to do with the biology or genetics of Blackness, but rather has everything to do with struggles against imperialism, everything to do with global struggles for a better world. But, of course, we continue those conversations.

And I’m actually impressed by the fact that increasing numbers of people are recognizing how important it is to have a decolonial or anti-imperialist perspective. If we did not expect to have abolition become a central element of public discourse during the early part of the 21st century — and it has become that — then I think we can be a little more optimistic about the possibility of encouraging people to think more critically about the future struggles against racism.

AMY GOODMAN: Angela, I wanted to ask you about this latest news. North Dakota’s Republican Governor Doug Burgum has signed legislation banning the teaching of critical race theory, so public schools are now barred from teaching students that, quote, “racism is systemically embedded in American society.” Critics say the law could ban the teaching of slavery, redlining and the civil rights movement. Even discussion of the law that was just passed is now prohibited in North Dakota’s schools. And you see this happening across the country. You know, I see Democracy Now! and, overall, independent media, one of its powers, aside from assuring that there’s a forum for people to speak for themselves, is bringing historical context to everything. So, when we talk about you today, in 2021, you constantly go back in time, and you look to the future. You talk about the struggles of the '60s and what's happening now. What about this movement against education in America?

ANGELA DAVIS: Well, Amy, I think that what we are witnessing at this moment is a profound clash between forces of the past and forces of the future. The campaign against teaching critical race theory in schools — now, first of all, critical race theory is not taught in high schools. And I wish more critical race theory were taught at the university level. But critical race theory has become a watchword for any conversations about racism, any effort to engage in the education of students in our schools about the history of this country and of the Americas and of the planet. Any discussions about slavery as the foundational element of this country are being barred, according to the proponents of removing, quote, “critical race theory” from the schools.

But let’s not be misled by the term they are using. What we are witnessing are efforts on the part of the forces of white supremacy to regain a control which they more or less had in the past. So, I think that it is absolutely essential to engage in the kinds of efforts to prevent them from consolidating a victory in the realm of education. And, of course, those of us who are active in the abolitionist movement see education as central to the process of dismantling the prison, as central to the process of imagining new forms of safety and security that can supplant the violence of the police.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Angela, I’m wondering if you could talk about the growing threat of fascism and authoritarianism here in the United States. Clearly, the January 6th events, I think, were a wake-up call to those who hadn’t awakened during the period of the Trump presidency. But the signs, not only in the United States but in much of Western Europe, are that the right-wing, fascist and populist — right-wing populist movements and fascist movements keep growing. Your sense of how progressives and radicals can unite to beat back this tide here in the United States?

ANGELA DAVIS: Well, of course, fortunately, we did manage to evict fascism from the White House. But I think that people are often a little too shortsighted and assume that by evicting the forces of fascism from the White House, that we had consolidated a victory. No, this is simply a skirmish, as Gramsci might point out, that we need to continue the effort to challenge a fascism that, of course, relies on racism in this country and white supremacy as the ways in which it expresses itself. There’s Brazil, of course, and we see continuing efforts to challenge, you know, what the terrible forces of fascism have done in that country.

I would suggest that here in the U.S., if we are serious about being victorious over fascism, that we have to have an internationalist perspective. We can’t simply focus on what is happening in Washington. We can’t simply focus only on our domestic issues. We have to have a greater understanding of what is happening in Brazil, in the Philippines, in South Africa, in Palestine, throughout Europe. And, of course, this is why we need Democracy Now! Democracy Now! helps us to place our own domestic issues and struggles within the context of global battles against fascism, against climate change, especially against climate change, against racism. We’re becoming aware that racism is not primarily a U.S. phenomenon, not primarily a South African phenomenon. It has infected our global atmosphere.

AMY GOODMAN: You know, you mentioned Palestine, Angela. And in 2019, you were very excited when the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute announced that you were going to get the Fred Shuttlesworth Human Rights Award. I mean, you come from Birmingham, and you were returning home, and it was going to be this big celebration. So we ended up following you back to Birmingham, but this was after the institute rescinded the award, reportedly due to your activism around Palestine. I mean, this became a major brouhaha. In the end, thousands of people — and we covered this whole journey you took — came out to the convention center to hear you speak, to show their support. The institute was disgraced. People resigned from the board. Ultimately, they reversed their decision, and you did get the Fred Shuttlesworth award. I mean, it was an amazing series of months, what happened. And I was wondering if you could talk about that and advice you have for others who have come under attack for their support of Palestine.

ANGELA DAVIS: Well, yeah, Amy, that was actually an incredible experience. And I am so excited now about the attention that Palestine has garnered in a place like Birmingham, Alabama. So many of the people who became involved in the effort to contest the decision of the board of the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute were not necessarily familiar with the struggles in Palestine. But in the process of recognizing that everyone deserves the attention of human rights activists, one cannot be in favor of human rights with the exclusion of certain communities or certain struggles or certain countries. And so I am excited to recognize now that people who were not necessarily involved in the campaign for justice in Palestine have joined that movement — Black people, Jewish people.

And as someone who’s been involved virtually all of my life in struggles around Palestine, as difficult as things remain — and we see the evictions continuing to take place. We see efforts to consolidate the rule of the Zionists, both there and — both in the region and throughout the world. But at the same time, there is, I think, more hope than we have experienced ever in the struggle for justice for Palestine, more people who are involved. And so, at first, I was so disappointed when I discovered that they were rescinding that award, but now I think, in many ways, that was a gift, because that generated conversation, and it generated a renewed reflection, collective reflection, on the absolute importance of focusing on justice for Palestine.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Speaking of reflection, you’ve been on Democracy Now! to talk about President Obama, you’ve been on to talk about President Trump, and then the Biden campaign, as well. And you said in 2020, “I do think we have to participate in the election,” but noted that in our electoral system as it exists, neither party represents the future that we need in this country. So, here we are now one year into the Biden presidency, the battles over these various — huge stimulus program concluding now, Build Back Better. The progressives are battling over what they should do if the Build Back Better program is further eviscerated. Your counsel to radicals and progressives about how they should deal with the Biden administration?

ANGELA DAVIS: Well, you know, those of us who voted for Biden and Harris did not do so because we expected to follow them as leaders in our struggle. We could have predicted this moment now. But I think that what we have learned, especially since the mobilizations of the summer of 2020, is that history does not change because a few leaders here and there decide to take particular positions or decide to pass bills. And, of course, I am not at all trying to minimize the importance of electing progressives and radicals both to Congress and to local office. I’m not at all disparaging that. But what I am saying is that in order to make real, lasting change, we have to do the work of building movements.

It is masses of people who are responsible for historical change. It was because of the movement, the Black freedom movement, the midcentury Black freedom movement, that Black people acquired the right to vote — not because someone decided to pass a Voting Rights Act. And we know now that that victory cannot simply be consolidated as a bill passed, because there are continual efforts to suppress the power of Black voters. And we know that the only way to reverse that is by building movements, by involving masses of people in the process of historical change. And that holds true for the current administration.

AMY GOODMAN: Angela, we’re still in the midst of the pandemic, and I’m wondering how it affected you over this past year and a half. As you talk about movements, so often it’s people gathering, whether we’re talking about the Critical Resistance conferences, the mass protests in the streets after George Floyd was murdered by the police. There were mass protests in the streets even during the pandemic, of course. But if you can talk about, just personally, what this meant for you and if you feel like we’ve learned something, everything from respecting science — and that goes not only from talking about vaccines but to climate change — the issue of vaccine inequity in the world, emphasizing those who have and those who don’t have in so many ways, but then also, personally, how you got by?

ANGELA DAVIS: Well, Amy, I am actually very fortunate in that I live in California. I live in Oakland. And I have access to the kind of technology that puts me in touch with people all over the world. So there are some things that I found really exciting about this terrible pandemic that claimed the lives of so many people, particularly Black and Indigenous and people of color and poor people, more broadly. What I might say was a kind of gift that was offered us in the midst of all of this sadness and tragedy was the fact that we can communicate with people all over the world. And so I participated in conversations that never would have happened had I been compelled to travel in order to be involved in these conversations — for example, a conversation in the Amazonas in Brazil that involved Afro-descended Brazilians, Indigenous Brazilians and people who are active in the struggle against police violence. So I think that there are some ways in which we consolidated our internationalism — of course, not consolidated, but we were able to engage in the kinds of practices that allowed us to recognize how important those ties are.

You know, on the other hand, of course we all need human community. We all need the closeness and the touch of human beings. And that has been so difficult.

I would also point out that I don’t know whether we would have achieved this kind of awareness of the nature of structural racism. And I don’t know whether so many people would have gone out into the streets, at their own peril, of course, because in the summer of 2020 we were not really clear about the ways in which the virus is transmitted. But I don’t know whether so many people would have felt compelled to go out and protest, if we had not become aware as a country — and I’m talking about a good majority of the population in the country — of the realities of structural racism. And the impact of the virus taught as about the nature of structural racism, as it had an impact on the healthcare system, as it claimed — as the virus claimed the lives of disproportionate numbers of Indigenous and Black people and people in the Latinx community. And that awareness helped to condition the response to the police lynching of George Floyd.

And so, as tragic as this period has been, as difficult as it has been to live without the closeness of our community, as terrible as that has been, it has also offered us some gifts. And I don’t know whether we would have experienced a situation in which more people than ever before in the history of this country went out in the streets and marched and protested and said no to racism.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Angela, I wanted to ask you — you mentioned earlier on Mumia Abu-Jamal. In our early years on Democracy Now!, we were knocked off the air in a bunch of Pennsylvania stations as a result of airing his commentaries. I knew Mumia personally because we worked together as journalists in Philadelphia in the early 1980s. I’m wondering — he has continued to be in prison, turned 67 in April, is 40 years now in prison. He’s had COVID, heart surgery this year. Could you talk about his importance? He’s one of the most famous political prisoners in the world. He has continued to have amazing commentaries and writings throughout his time in prison. Mumia’s impact on the radical movement in America? And if you could talk about the pressing need to continue to demand his release?

ANGELA DAVIS: Yes. Thank you so much, Juan. I don’t think we would be where we are today without the consistent and dedicated participation of Mumia Abu-Jamal in our struggles. Well, first of all, I would say that Mumia is known all over the world. There are streets named after him in Germany and in France. He became the second person in the history of France, after Pablo Picasso, to receive an honorary citizenship in the city of Paris, and so that his importance is recognized elsewhere in the world. But because of the ways in which the police and the police benevolent order, the Fraternal Order of Police, because of the ways in which they have misrepresented Mumia and mobilized the entire police community all over the country against Mumia, he remains in prison, after having served time for more than 40 years, including much of it on death row.

What I would say now is that precisely because we have succeeded in making public critiques of the police — and, of course, we see them now trying to reconsolidate their power all over the country, but because there are these fissures in the power of the police, we should take advantage of that to intensify the campaign to free Mumia Abu-Jamal. I was just communicating the other day with Julia Wright, the daughter of Richard Wright, who has been so important in France in developing the campaign to free Mumia. And she and people all over the world want to see us bring the case of Mumia to the fore, especially now, considering the fact that David Gilbert, who has been in prison almost a half a century, was released on parole recently, two weeks ago. We have to claim that victory and recognize that this is precisely the moment to demand more releases, to demand the release of Leonard Peltier, who has been in prison even longer than Mumia, and all of the political prisoners who remain behind walls.

AMY GOODMAN: People can go to Democracy Now! and see our interviews with Leonard Peltier. I know we have to wrap up, and it’s very hard for me and Juan to stop this conversation, but — and we’re going to talk to you again on Democracy Now! Your book is coming out again, it’s being reissued, Angela Davis: An Autobiography, which astoundingly was edited by Toni Morrison. We talked to you on Democracy Now! when Toni Morrison died. We talked to you when Aretha Franklin died. We tracked you down, I can’t remember where. And it’s amazing, because while people talk about Aretha’s great artistry, what people didn’t realize is that she was involved with offering to post bail for you when you were in prison, saying, “Black people will be free.” And I’m wondering if you can reflect — we’ll go much more extensively into this when your book comes out — on these relationships you have had and what gives you hope for the next generation of artists, writers, scholars and activists, all of which you are, rolled into one.

ANGELA DAVIS: Well, you know, I think that having — I think that having lived this many decades and having experienced what I have in the context of movements against racism and against heteropatriarchy, against imperialism, I am more committed than ever to using what talents I might have to developing movements for radical change.

And you mentioned Aretha Franklin and the fact that she offered to post bail for me. That was a very moving moment in my life, and I have come to recognize how absolutely essential the role of artists has been and will be for our movements. This is a period during which musicians and visual artists, poets, writers are all using their talents collectively to create more possibilities for the kinds of conversations that will bring people into movements for justice, for freedom, for equality.

And let me say one more thing, which, unfortunately, we haven’t discussed during the course of this wide-ranging conversation, and that is the power of global capitalism. And I still see that we need — I still think that we need artists to show us the way toward a very different organization — economic, political, social organization — of our worlds, and capitalism has to fall.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, Angela Davis, we want to thank you so much for being with us. And I want to ask you, finally, about the issue of independent media, of people shaping their own narratives. I mean, I think that’s the power of the corporate media, is they tell a story, whether it is true or not, brought to you by the weapons manufacturers every five minutes or the drug industry every 10 minutes, you know, the commercials, as you talk about capitalism. If you could talk about a different kind of media in, perhaps, if you want to imagine this, a post-capitalist society and what that would offer, since it’s the way people can communicate with each other all over the world?

ANGELA DAVIS: Well, I think it’s so important now, Amy, to imagine new worlds. We cannot fight for those worlds unless we know how to imagine them. And independent, progressive media, like Democracy Now!, help to inspire us in that project of collective imagination to allow people to tell their own stories. And, of course, you go where the movements are unfolding. I’ll never forget watching your arrest at Standing Rock and how that campaign helped to galvanize a more holistic understanding of what it is we’re struggling for, the freedom that we’re fighting for, that we have to save this planet. And Indigenous people, the stewards of this land for so many millennia, have taught us that the struggle for the environment has to be central to our work. And you present their stories. So I thank you and Juan and all of your colleagues for the work that you continue to do. And I’m sure we’ll be speaking to each other in the near future.

AMY GOODMAN: World-renowned abolitionist, author, activist and professor Angela Davis.